ICTY: THE KOSOVO CASE, 1998-1999

How the Crimes in Kosovo Were Investigated, Reconstructed and Prosecuted

This presentation contains material that some viewers may find disturbing.

PROLOGUE

A Crime That Was Waiting to Happen

The political crisis that had been developing in Kosovo from the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s culminated in an armed conflict between the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and Serbia and the Kosovo Liberation Army, or KLA, from mid-1998. During that conflict there were incidents where excessive and indiscriminate force was used by the Yugoslav Army (VJ) and Serbian Police units of the Ministry of the Interior (MUP), resulting in civilian deaths, population displacement and damage to civilian property. Despite efforts to bring the crisis to an end, which included sending an international verification mission to Kosovo, the conflict continued through to and beyond 24 March 1999, when NATO forces launched an air campaign against targets in the FRY. The bombing campaign ended on 10 June 1999, followed by the withdrawal of FRY and Serbian forces from Kosovo.

Excerpts from Trial Chamber judgement in Šainovic et al case

Selection of documents

INVESTIGATION

The Delayed Crime Scene Investigation

In a departure from the usual practice of not commenting on ongoing investigations, on 10 March 1998, Louise Arbour, Chief Prosecutor of the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia), publically announced that her Office was ‘gathering information and evidence in relation to the Kosovo incidents’ and that she would ‘continue to monitor any subsequent developments’.

Three weeks later the UN Security Council in its Resolution 1160 (31 March 1998) urged the Office of the Prosecutor to ‘begin gathering information related to the violence in Kosovo that may fall within its jurisdiction’ and reminded the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) authorities of their obligation to cooperate with the ICTY.

These warnings and condemnations had no effect and on 23 September 1998, the Security Council responded with Resolution 1199, stating it was ‘deeply concerned’ by the escalation of violence in Kosovo and appealed again to the FRY authorities and Kosovo Albanian leaders to ‘cooperate fully with the Prosecutor of the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia’.

On 5 October 1998, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan issued a report stating that ‘it is clear beyond any reasonable doubt that the great majority of such acts have been committed by security forces in Kosovo acting under the authority of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’. The FRY authorities, which until Annan’s report had tolerated the presence of ICTY investigating teams in Kosovo, now completely banned investigators from visiting crime scenes in the province.

Selection of documents

THE PATTERN OF CRIMES

The Last Exodus of the 20th Century

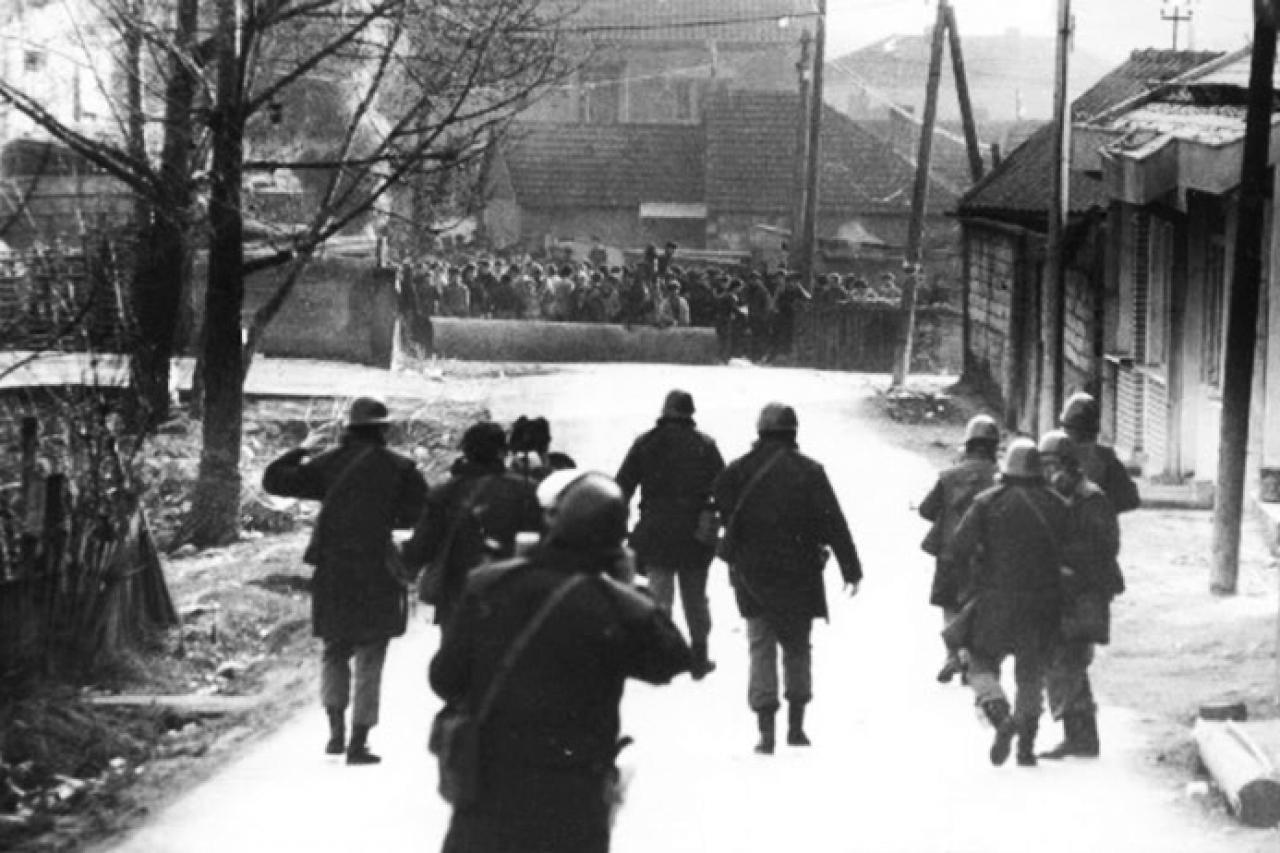

From around l Јanuary1999 and continuing until 20 June 1999, forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and Serbia perpetrated numerous crimes which resulted in the forced deportation of approximately 800,000 Kosovo Albanian civilians.

То facilitate these expulsions and displacements, armed units of the FRY and Serbia deliberately created an atmosphere of fear and oppression through the use of force, threats of force and acts of violence. Attacks on civilians followed a pre-determined pattern that involved the shelling of towns and villages, destruction of residential and religious buildings, the killing of women, children and men not directly involved in hostilities and sexually assaulting Kosovo Albanian women. Those actions were carried out across Kosovo and the same intentional means and methods were used throughout the province.

The expulsion of Kosovo Albanian civilians was carried out with the aim of changing the ethnic makeup of Kosovo and thus establishing the full control of Serbia’s authorities over the province.

Evidence on the expulsion of civilians from 13 Kosovo municipalities was called during trials at the ICTY.

(Excerpts from the indictment in the case against Milutinović et al.)

Selection of documents

MASS MURDERS

Those Who Survived Kosovo Killing Fields

From about 1 January 1999 until 20 June 1999, the military and police forces of the FRY and Serbia murdered hundreds of Kosovo Albanians who took no active part in the hostilities. The murders were perpetrated in a widespread and systematic manner throughout Kosovo and resulted in the deaths of many men, women and children.

In most of these locations, such as Krushë e Vogël/Mala Kruša, Izbicë/Izbica, Bellacërkë/Bela Crkva, Gjakovë/Đakovica and Qyshk/Ćuška, the victims were men, but in a certain number of incidents, such as in Suva Reka and Podujevo, the perpetrators killed women and children. The worst single crime in Kosovo occurred in late April 1999, when about 350 male civilians were killed in Mejë/Meja, Korenicë/Korenica and other villages around Gjakovë/Đakovica in the course of Operation Reka.

The ICTY investigation covered a minor part of the murders of Albanian civilians in Kosovo - approximately 20 locations where between 700 and 800 victims were killed - the point was to highlight the pattern of the attacks on the Albanian population, not to record all the crimes and identify all the victims.

Selection of documents

HIDING THE EVIDENCE

No Corpse – No Crime

On 26 March 1999, two days after NATO launched its air strikes, the ICTY Chief Prosecutor Louise Arbour sent a letter to President Slobodan Milošević and twelve other political, military and police officials of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and Serbia warning them that she would be following events in Kosovo closely as part of Tribunal’s mandate from the UN Security Council. Arbour also reminded the Serbian and Yugoslav officials that they were obliged under international law to prevent war crimes or to punish subordinates who committed such crimes.

After the warning from the ICTY, a series of meetings of the highest Serbian and Yugoslav political and police leadership levels were held in Belgrade, aimed at seeing how they could prevent ICTY investigators from The Hague – who were bound to show up in Kosovo sooner or later – from searching for evidence of crimes committed there.

According to the diary of one of those attending the meetings, Police General Obrad Stevanović, the method by which traces of crimes would be removed and that those present would be protected from criminal liability was devised by President Slobodan Milošević himself.

Selection of documents

JUDICIAL EPILOGUE 1

Beyond Reasonable Doubt

The crimes against Kosovo Albanians in 1999 were the subject of three ICTY trials: Slobodan Milošević, Milan Milutinović et al., and Vlastimir Đorđević. The former president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), Slobodan Milošević died in custody before his trial ended and the other two trials resulted in judgments in which one of the accused was acquitted and six other high-ranking political, military and police officials of the FRY and Serbia were found guilty.

In both trials, the judges concluded that in 1999 there was a joint criminal enterprise whose goal was to change the ethnic balance in Kosovo by expelling Albanians in order to strengthen the hold of the FRY and Serbian authorities over the province.

Although he did not see the end of his trial, Slobodan Milošević is named in the judgments in the Milutinović et al. and Đorđević cases as a participant in the joint criminal enterprise.

Selection of documents

OBSTRUCTING THE INVESTIGATION

Too Many Obstacles, Too Little Evidence

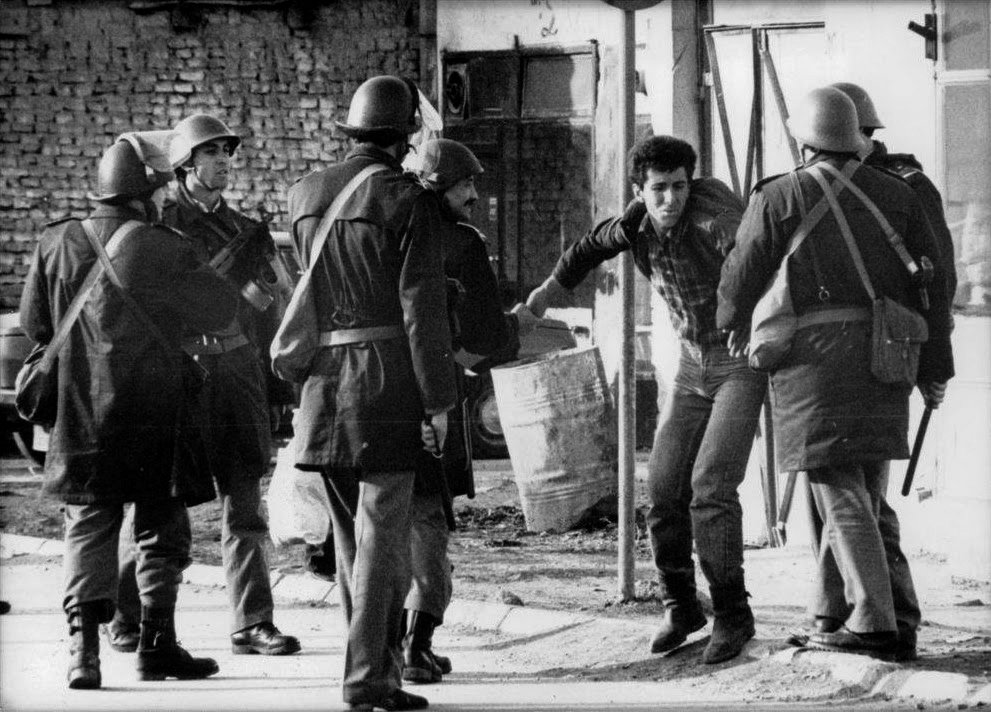

The Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) of the ICTY first began looking into crimes committed in Kosovo in the spring of 1998 after the Serbian police special forces raid on the compound of Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) founder Adem Jashari in the village of Donji Prekaz, when Jashari and almost 60 members of his family were killed. The ICTY prosecutor had first to establish whether the fighting in Kosovo qualified as an internal armed conflict – a prerequisite for establishing ICTY jurisdiction and enabling it to prosecute those responsible for crimes against humanity and violating the laws and customs of war.

Having concluded that the KLA was an organised military formation and that an internal armed conflict was going on in Kosovo, the OTP focused in mid-1998 on investigating the role and responsibility of Serbian political, military and police leaders, then led by the president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milošević. An indictment against Milošević and five of his close associates for crimes committed in Kosovo was issued in May 1999.

OTP investigators entered Kosovo in July 1999, on the heels of the international peace-keeping force (KFOR), and soon extended their enquiries to the alleged crimes committed by the KLA against Serbs, Roma and Kosovo Albanians suspected of collaborating with the Serbian authorities. The first indictment against KLA commanders was issued in January 2003.

THE MISSING LINK

A Chain of Command without Commanders

Before launching a formal investigation in the spring of 1999 into the events in Kosovo, the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICTY (OTP) concluded that violations of international humanitarian law in this territory fell under its jurisdiction, since they had been committed in the context of an internal armed conflict between two organized military forces, both of which had functioning chains of command.

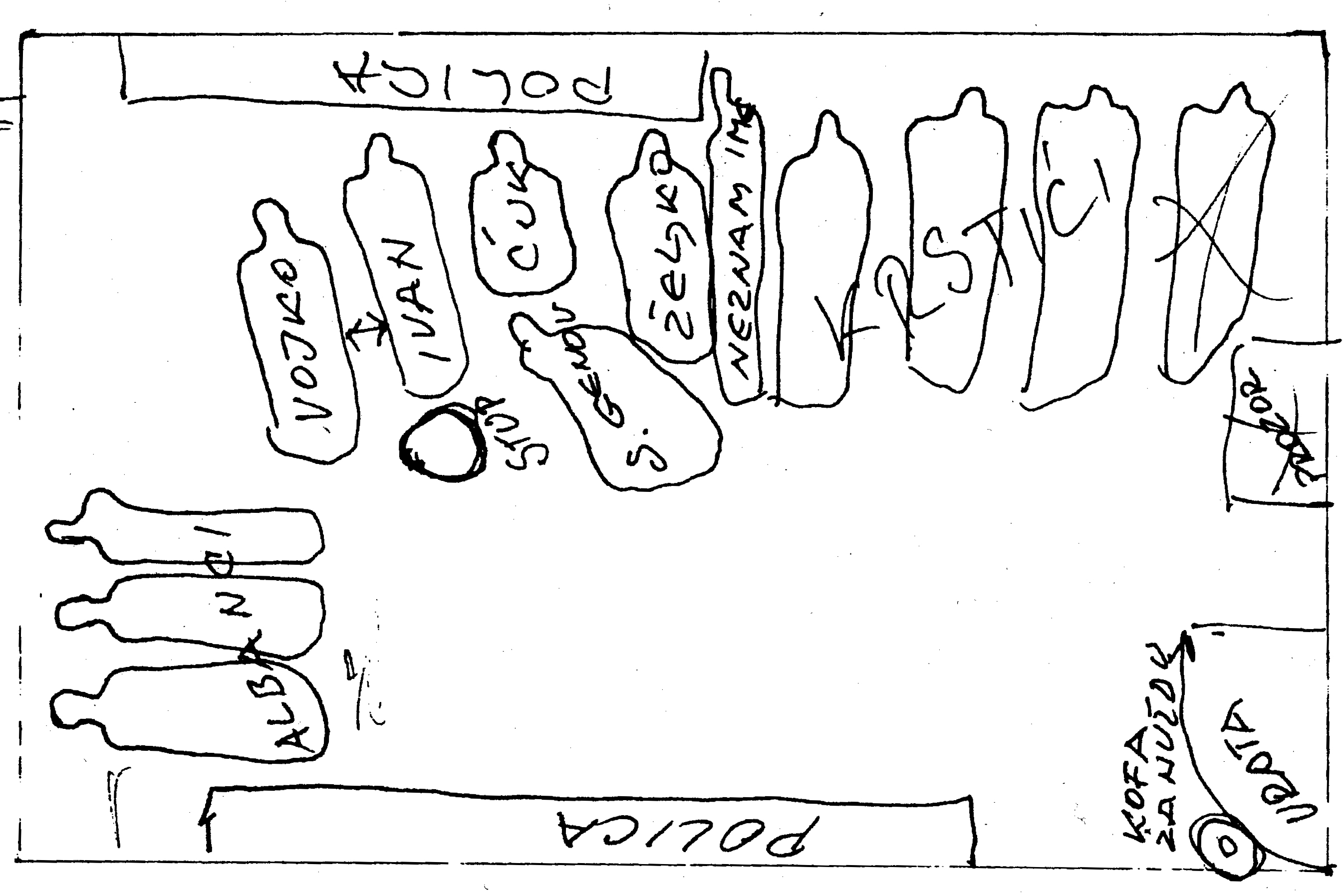

The OTP’s charges in the cases of Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) commanders, Fatmir Limaj and Ramush Haradinaj and four of their subordinates, were largely based on the testimonies of victims and witnesses, and forensic evidence collected during the investigation and exhumations in the field, and on the testimonies of the so-called insiders – former KLA commanders – who in their interviews with ICTY investigators openly talked about how zones of responsibility were established in Kosovo in 1998 and who commanded certain zones at certain times.

However, when it came to repeating this this in court, the former KLA commanders changed their statements and claimed that the chain of command in the zones of responsibility of the accused was established after the period referred to in the indictment: May to July 1998. They claimed that the chain of command started in the autumn, after the formation of brigades and battalions, and therefore after the crimes they were charged with had been committed.

A link was thus removed from the chain of command, a link which would have allowed the ICTY prosecutor and the judges to connect the accused commanders of the zones and units of the KLA with the direct perpetrators of crimes against Albanian, Serbian and Roma civilians.

Selection of documents

JUDICIAL EPILOGUE 2

Reasonable Doubt

The crimes committed in 1998 by Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) members against Serbs and Roma, and against Albanians suspected of ‘collaborating’ with the Serbian authorities, were dealt with in two cases before the ICTY: Limaj et al and Haradinaj et al.

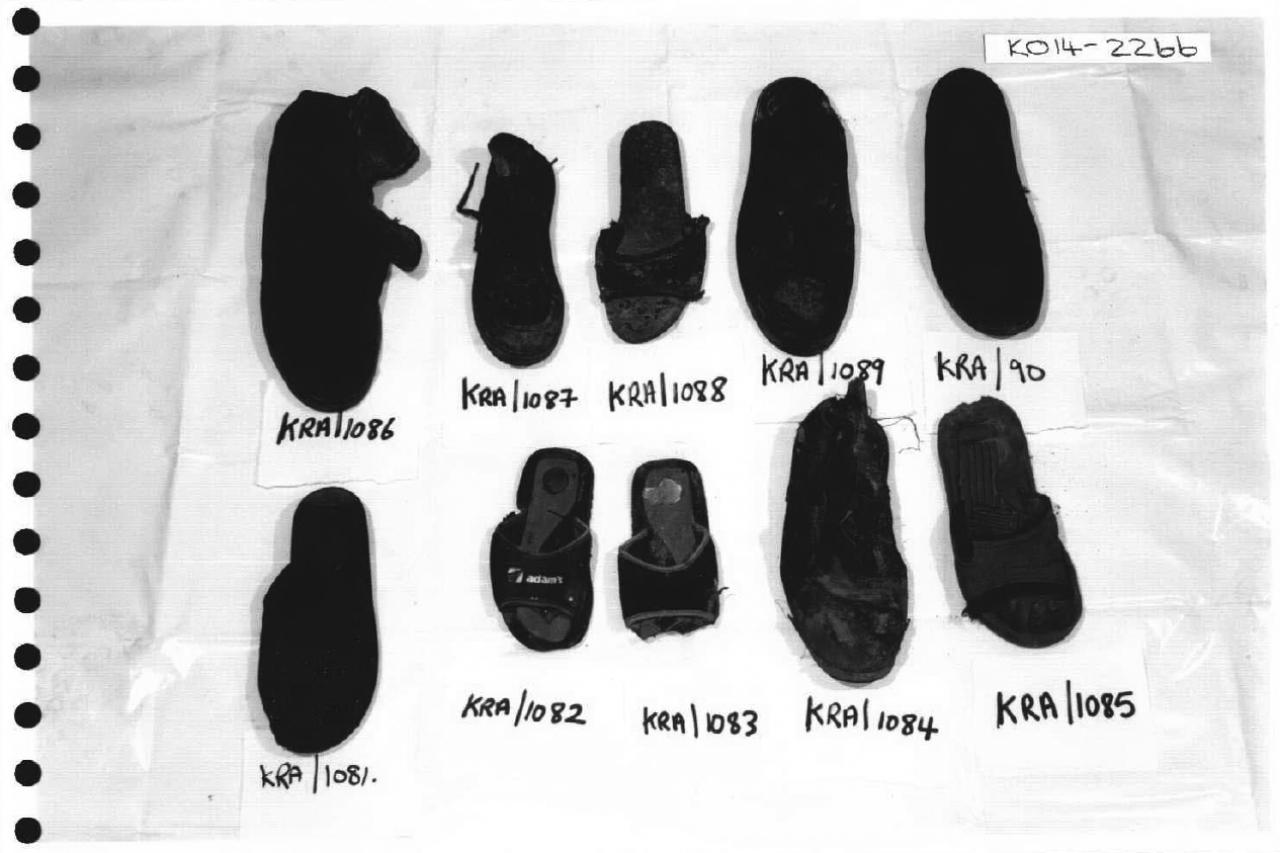

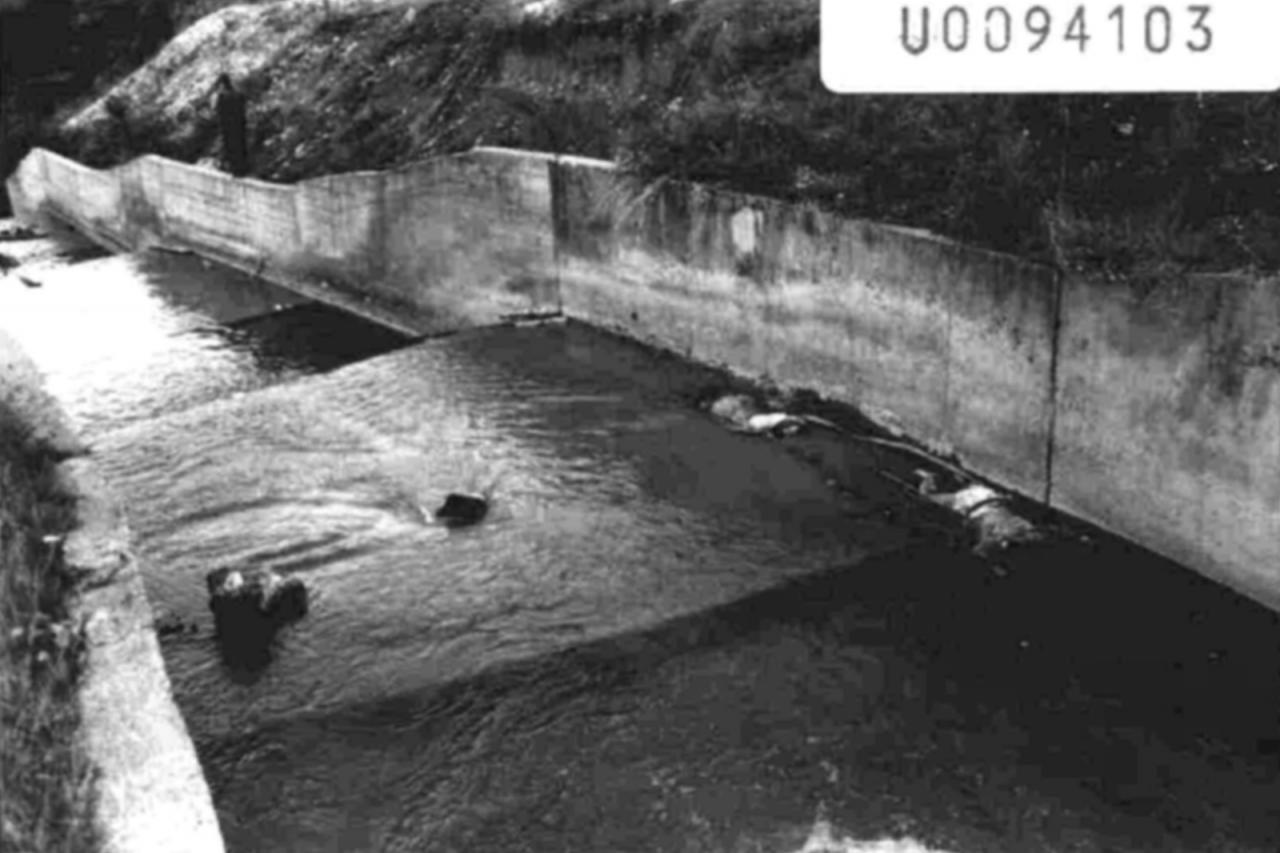

The judgments concluded that the crimes alleged in the indictments had been committed, and that KLA members were responsible for a number of them, including the abuse in Llapushnik/ Lapušnik and Jabllanicë/ Jablanica camps, the murder of civilians on Berishe/ Beriša Mountain and the murder of seven of the 30 people whose bodies were found in the Lake Radoniqit/ Radonjić canal.

Although the prosecution managed to prove that the crimes had occurred and that the KLA was responsible for them, it failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt the link between the direct perpetrators and the accused KLA commanders. Nor did it prove the existence of a joint criminal enterprise whose goal was to strengthen KLA control over parts of Kosovo through a campaign of crimes against civilians. This failure had several causes: a lack of documents showing the KLA structure, the questionable credibility of the evidence obtained from Serbia, mistakes made by the investigators in the field and problems with witnesses during the course of the trial.

The judgment in Haradinaj et al. states that the trial proceeded ‘in an atmosphere where witnesses did not feel safe’ with many witnesses citing fear as a prominent reason for not wishing to give evidence. Similar witness issues marred the Limaj et al. trial. A number of contempt of court indictments were issued because of attempts to intimidate witnesses and reveal their identity in public, or because of their refusal to testify.